GQ (Août 2001)

Caractéristiques

-

Edition :Physique

-

Publié en :Août 2001

-

Pays :United Kingdom

-

Série :

Photos

Retranscription

Heroes

Icon Robbie Williams

Occupation Glee dealer, ladykiller, superstar

He’s Mr Charisma, the clown prince of British pop. He squires the loveliest ladies and his records sell millions. But can Robbie Williams live without fame? Adrian Deevoy spent a year with him to find out. Portrait by Jake Chessum

Without wishing to sound too affected, I’m going to call him Rob. This, I must stress, is not borne out of any music business first-syllable-term overfamiliarity. Rob and Robbie are distinctly different blokes. They’re one, as Bono sang, but they’re not the same.

Robbie is the cunningly constructed, quip-lipped, omnipresent megalegacy we have come to love as The Ironic English Elvis. An electrifying entertainer endowed with such supersonic self-confidence and casual charisma that he can never quite decide whether to bare his soul or his buttocks. Mr Fags, Footie and Five-Times-A-Night. We all know Robbie well enough.

Then there is Rob, the beguiling creator of this postmodern pop monster. He is a compelling confusion of nagging doubt and blinding ambition, a curious crossbreed of crown prince and class clown. A man of many parts – some of them even private.

Rob smokes like a lifer, nibbles his nails and gets tongue-tied around pretty women. He blushes when he’s out of his depth and feels like a girl about his looks. He jokes about one day getting a satin flight jacket marked with the “Head Of Insecurity” on the back.

He grew up in a Potteries pub and could pull a pint aged three. He could probably sing all the songs from Oliver! too. He was a cute kid with a taste for mimicry and a devilish twinkle in his eye. His lashes were so long Bambi was said to have been fiercely jealous.

It was inevitable that Rob would be drawn toward the spotlight. His dad was a stand-up; it was in the blood. By 16, Rob was doing the working men’s clubs. The men happened to be mostly homosexual and Rob wasn’t normally wearing trousers but, hey, he figured, that’s entertainment.

“Being famous has become my job,” Britain’s most recognisable man muses in the car one morning. “I wouldn’t like not to be famous.” It should be mentioned that, such is his Zen-like acceptance of fame, he is one of the few internationally renowned stars who travels with the tinted windows wound down. “I don’t want to be unfamous,” he says, pleased with the new word, pronouncing it as if to rhyme with “infamous”. “Being unfamous would be too weird for me now.”

Of course there are days when he’ll pull the hood of anonymity, the better to blend into the background. But for the most part he works the role like a music hall pro. “Can I have an autograph for my sister?” asks a young mum. “Seems like a fair swap,” he says, groaning audibly as the threadbare line leaves his lips.

But he still gets a buzz from queuing for a skinny mocha in his local Starbucks then drinking it outside because taht way, not only does he get to have a cigarette, he can also watch the world watching him. Rob plays his public brilliantly, invariably sending them away with a spring in their step and a what-a-lovely-guy,smile. Even when a bunch of burly builders chorus, “Robbie, you caaant!" he fixes the biggest one with his cheekiest smirk and says, “Oh, that is nice" It's then you remember that he has been famous for longer than he's been shaving.

Robbie will kill you with kindness – anything to keep you at arm’s length

Egolden boy

Robbie is apt to erupt at Stamford Bridge, June 1999. Below: one of Robbie’s many low points – this Christmas ’98 break-up with All Saint Nicole Appleton

Entering Rob’s world of unnatural normality, you initially feel over-protective and under suspicion. You sense him thinking, "What, precisely, do you want from me?” Are you a groupie, a stalker or just another two-bit coke dealer?" And although his antennae are finely tuned, plenty of chancers have slipped under the net, got him pissed, kissed and told, tried to turn him over. Run into Robbie these days and he'll kill you with kindness and charm your cashmere socks off - anything to keep you at arm's length.

Meeting Rob generally runs like this: first there's a manly Mafia hug, possibly a stubbly Sicilian kiss, then he hits you with the searching, sensitive stare - a device he knows full well can deeply-fry a female heart at 40 paces. Without dimming the headlights, he will enquire warmly as to your physical and spiritual wellbeing while reading your eyes for clues, because no one says what they really mean anymore. There will follow a surprisingly perceptive question about your recent life: an ingeniously retrieved sliver of seemingly unimportant information; a tiny personal detail recalled. He will usually combine this with a flattering reference to your appearance or a cheeky gag about your mother. He will then share a piece of priceless gossip, or unleash some actionable showbusiness secret.

And all the while this is happening, you constantly remind yourself that you’re probably witnessing a well-rehearsed routine – falling victim to the oldest trick in the charm-school manual. And yet every time you meet Rob it’s like citing tight shoes. It truly is that pleasurable.

But when the force field fades, you find a complex individual as vulnerable as a Battersea stray, living his life in a perpetual state of raw emotion and need.

You get an occasional glimpse of this skinlessness in his lyrics. As one commentator noted, his songs only ever say, “Aren’t I great?” or “I’m not that great, am I?” In the flesh, Rob embodies this conundrum. At the risk of sounding like an armchair psychologist, the boy is up and down like a bride’s nightie.

The first time I was subjected to the charm offensive was at a party thrown for the editor of GQ at the Groucho. Uninvited and lightly “refreshed”, Rob pitched up late and stayed for the duration. The nuances had a lived feel, but I do remember a discussion we had about astrology. He believed, and I didn’t, that the date you were born could somehow govern your life. But that was not what made the debate interesting. Infinitely more intriguing was that Rob conducted the entire conversation – and you couldn’t help but notice this – while standing on his head. Regardless of what you felt about his music or his public persona you came away from the encounter thinking: “What a thoroughly excellent human being.”

Scroll forward three years and Rob is lying on his floor of his apartment on a 21st-century bachelor pad if ever one existed – rearranging his knackers and laughing at the memory. “I was standing on my head, wasn’t I? What the fucking hell was that all about?” Chris Sharrock, Liverpool’s third best drummer and Rob’s occasional lodger, is in the kitchen making reports on northern tea. He rolls his eyes heavenwards.

Having discovered Rob at uncomfortably – often unhygienically – close quarters, he is no stranger to such high jinks. There was the Rob walked out on stage bollock naked. The gig in Hull where he was so incoherent the show had to be cancelled. The night a copper arrived only to find the singer stripped to the waist, in full eye make-up, attempting to make a complaint about neighbourhood safety. And that’s not to mention the bonding sessions with the precocious starlet, the courtship of the Irish folkie or the unsavoury story which took flight in L.A. on the immoral confession, concluded with:

“I shagged Greenpeace.”

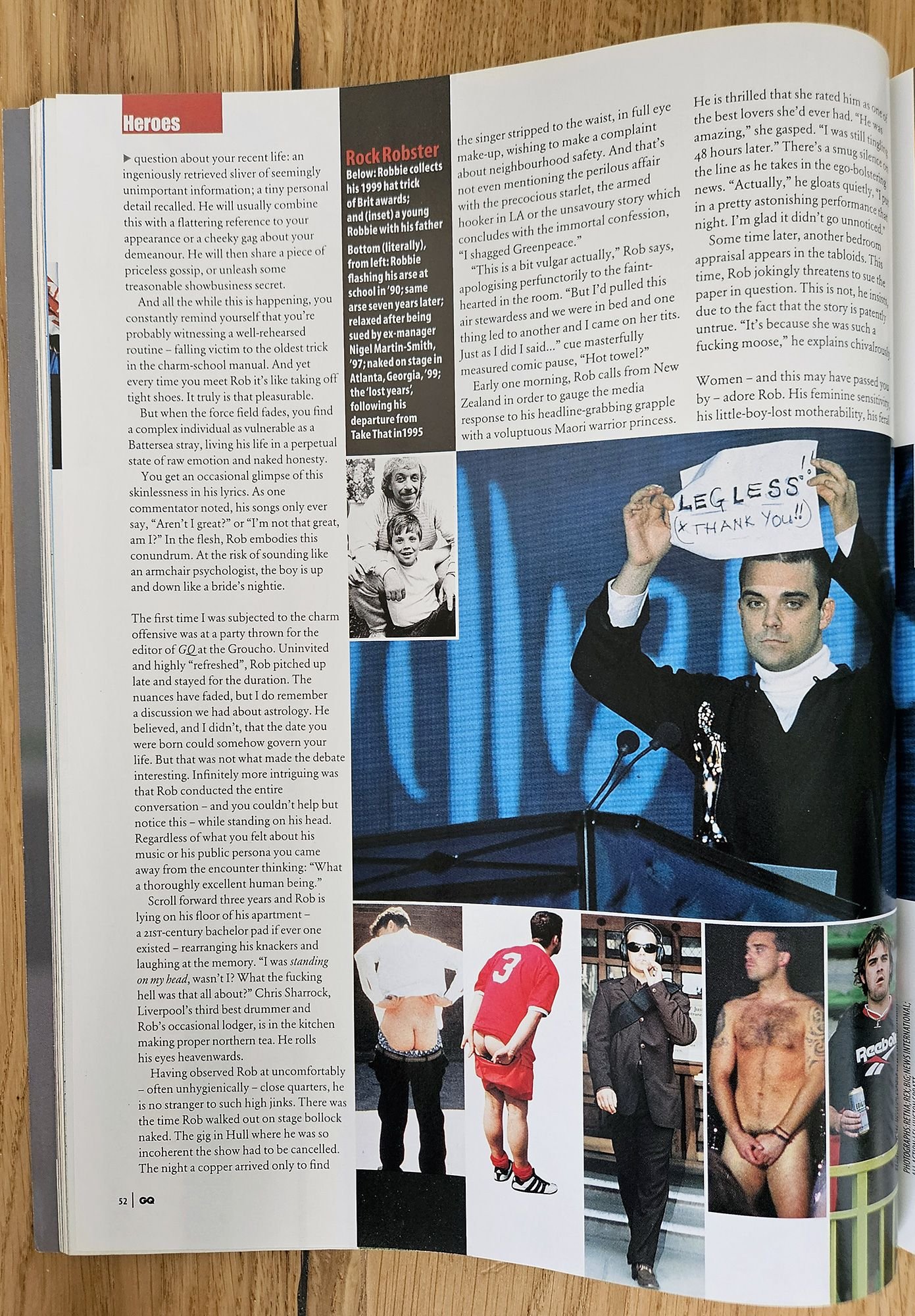

Rock Robster

Below: Robbie collects his 1999 hat trick of Brit awards (and instead shows it).

Above left: Robbie with his father.

Bottom (literally), from left: Robbie flashing his arse at Soccer Six in 2000; reveals all after being tackled at the same event in 1999; naked on stage in Atlanta, Georgia, 1999; the “lost years”, following his departure from Take That in 1995

“This gets a bit vulgar actually,” Rob says, apologising perfunctorily to me and the airless in the room. “But I’d pulled this fit stewardess on a short-haul and she started to wonder how I came on to her. You know… and I went carefully – just as I did I said… ‘Hot towel?’”

Early one morning, Rob calls from New Zealand in order to gauge the media response to his headline-grabbing grapple with a voluptuous Maori warrior princess.

He is thrilled that she rated him as one of the best lovers she'd ever had. "He was amazing," she gasped. "I was still tingling 48 hours later." There’s a smug silence on the line as he takes in the ego-bolstreing news. "Actually" he gloats quietly, "I put in a pretty astonishing performance that night. I'm glad it didn't go unnoticed."

Some time later, another bedroom appraisal appears in the tabloïds. This time, Rob jokingly threatens to sue the paper in question. This is not, he insists, due to the fact that the story is patently untrue. "It's because she was such a fucking moose," he explains chivalrously.

Women - and this may have passed you by - adore Rob/ His feminine sensitivity, his little-boy-lost motherability, his feral sexual magnetism. They know that he will be upfront about his feelings, but they understand that he'll still take them roughly from behind. His effect on the fairer sex is fascinating to behold.

To illustrate: one lazy afternoon we're tooling around Kensington, listening to gangsta rap in a borrowed Bentley, when Rob decides it would be fashionably gauche to dangle a pair of furry dice off the rear-view mirror of such a distinguished vehicle. As serendipity would have it, a girl in a VW Golf pulls level at the lights with the most magnificent set of dice. By extraordinary coincidence she is listening to a Robbie Williams album. Rob leans out brandishing a ten pound note and offers to buy the dice on the spot. The girl looks perplexed, yet feverish if she has awoken from an erotic dream. "But I was just listening to you," she says in a faraway falsetto. "I want to buy them," Rob repeats in the lights turn amber. She rips the dice down and hurls them into our car as Rob strains to hand her the tenner. The last we hear is her distant voice mumuring, "Oh God, what's going on?" as she all but careers into the central reservation. We speed onwards laughing like idiots, Tupac blaring, dice hanging proudly.

Jump-cut to the Buddha Bar in Paris. Rob is treating a group of friends to dinner and makes his entrance looking, even if he says so himself, the nuts. Dove-grey Richard James overcoat draped, Sopranos-style, over the shoulders of a black Gucci suit, he walks in cinematic slo-mo to his table. As his co-writer Guy Chambers always says, “Rob certainly knows how to make an entrance.” Positioning himself between two not-unattractive girlfriends, he turns down his mouth and turns up his palms in the time-honoured Corleone tradition. Then, in that curiously camp Stoke accent, he says to the waitress:

“I want an extremely alcoholic cocktail that doesn’t taste at all of alcohol.”

Rob’s rollercoaster relationship with drink has been documented in microscopic detail. In truth, he’s a dreadful drinking partner in that one is too many and a thousand aren’t enough. I’ve only seen him incredibly drunk on one occasion. It was the evening that went down in anecdotal history simply as “Newcastle”.

Earlier we had been to St James’ Park where Rob displayed all the tact and diplomacy of a vote-hungry backbencher (at one point he kissed a baby while simultaneously glad-handing a pensioner), then went on to play a superb concert at the local 16,000-seater. In celebratory post-show mode he drank a couple of stiff Sambucas, flirted shamelessly with Alan Shearer’s wife and most roundly berated Gary Speed for that most heinous of crimes: being Welsh. He then finished off his bottle of foul liqueur, cracked open another and announced that he wanted to go clubbing down on the docks. Having selected the most densely populated and potentially murderous bar, he attempted to engage a bemused Chris Waddle in a surreal one-sided conversation (Rob’s contribution was to periodically cry, “The Waddler!” while hopelessly attempting to embrace the unfortunate footballer). Midway through the exchange, Rob blacked out and went down like a sack of spuds, only to re-emerge moments later animatedly chatting up the girlfriend of the meanest-looking pirate in the place.

The night ended in a manner that would have made Keith Moon envious. Dressed, for reasons known only to himself, in full golfing regalia, Rob wound up at 6am drinking tequila in the back room of a bar with a tramp for company. The following evening, the only words the hungover singer could muster were, “New levels of self-loathing” before stumbling back to bed.

On a miserable motorway a few days later, a rejuvenated Rob wonders, “If you could invent a drug that made you feel better than you’ve ever felt and had no side-effects and no comedown at all, what would it be called?” We decide upon the word “Glee.” Over the ensuing weeks it becomes a byword for happiness. Sometimes you might feel as if you’ve done a lot of Glee. Even too much.

One evening on stage, Rob turns to the wings, mid-song, and mouths, “I’m full of Glee!” Other times you might have just done a half. Then there are days when you haven’t seen the Glee dealer at all. Rob even comes up with a binary drug code to describe the ordinary two component effects of Glee being — appropriately enough, it’s called “Sad.”

“What does it all mean?” he puzzles, surveying another crammed arena on his colossally joyous tour. “I mean, really, what’s all this about? I suppose it hasn’t anything to do with me.” Touring generates, actually, he says, if not new songs, then a heaving section of new seating. “That means a new bathroom. And that means a new toilet. And that means new gold taps. Back in it has meaning.”

Back at the dressing room, Rob plays a few pieces from the songs he has written. The lyrics, which address his relationship with his dad, are almost too painful, such is their forthright frankness. To be honest, it reduces us to tears.

Later he puts on a love song he’s written about Geri Halliwell that elicits a similarly saline response. I should confess here that I think Rob is a superb lyricist. He cringes with embarrassment and flushes with professional pride if you even suggest to him that had Bob Dylan written "Angels" it would be considered a work of unparalleled genius. Or if “Better Man” were a cover of a John Lennon song and not a Williams / Chambers original, we would be marvelling at the economic structure and pared-back poignancy of the lyric.

Not that he is above ripping off the masters. His respectful pillaging of Ian Dury's "Reasons To Be Cheerful" and A Tribe Called Quest's "Can I Kick It?" is a matter of public record, but it can be a sly magpie, too.

One evening after a few drinks, we are singing a heartfelt duet of Elvis Costello’s “Shipbuilding” when it suddenly dawns that Rob has filleted that one, too. "You wouldn't believe where I've nicked stuff from," he smiles enigmatically, and with that nips off to the kitchen for a strategically timed top-up.

To amuse ourselves on another quiet night in we watch an old Take That video, and are amazed at the well, overt gayness of the whole affair. Still besieged by mixed emotions, Rob is attempting to explain the birth of the British boy band phenomenon to a baffed American. “It was first-item news when I left the band,” he blurts. “Actually, I point out rather pedantically — ‘you didn’t leave, you were sacked.’” “Oh yeah,” he frowns, “forgot about that. But this item’s new.” Now on permanent rotation is his appearance in The Royle Family, Chris Sharrock dryly confirms this fact. “Yeah, it was. Trevor McDonald, the works. That show’s so popular.” His employer smiles self-deprecatingly. He prides himself on being a fair boss that lets colleagues abuse golf buggies and yet demands excellence. He has, however, recently introduced a caveat known as “C****unt Rights.” An example: Rob pitches up at a TV station and asks an assistant if they could find him some sushi. They say, of course, sir. Thirty minutes elapse and the keenly anticipated Japanese snack still hasn’t arrived. The increasingly peckish artist becomes mildly agitated. Then he’s drumming his fingers and hummers psychotically. After 35 minutes he announces, “C****unt Rights!” — this being when he opens the unequivocal floodgates like a spoilt pop star — and throws a full-scale prima donna tantrum. Like Joe Cocker in a hurricane, you don’t see these often but when you do they’re especially memorable. He’s always full of remorse afterwards. Sushi failure guarantees he’s full of sushi, too.

Holed up in a country mansion in Bath, to alleviate the boredom of band rehearsals, Rob organises an impromptu football tournament on the croquet lawn. Before kick-off, players remind themselves there are no touring musicians and that nobody must take it easy on the pitch. The object is formality of tone. Rob is the referee and like most keepers of order, tends to kick lumps off anybody who questions his authority.

Unsurprisingly, Rob plays up front. He’s an intelligent player with a turn of pace, a dancer’s balance and an accurate right foot, but falls down when he has to hold the ball. He’s a shooting opportunist, but lacks the showmanship, style and stamina of the true striker.

Little love is lost during the game. Elbows fly, tempers flare, Robbie relishes the heat more than any blues. Flexible, aggressive, hacking at Rob’s ankles and growling like a Tube station drunk. We win by a narrow margin, but dinner that night is a strangely subdued affair.

On the way back to London the following afternoon, we stop by a service station bush so that Rob might enjoy an alfresco wee. Public peeing is the latest thing. It is, he believes, "pubk rock".

"Do you know?" he says in full flow, "I think I only want people to fall in love with me just so I can leave them."

It's a saddening admission and one full of shame and regret. He buttons up pensively and sighs softly. "Great being me, istn' it?"

After this summer's stadium shows, which will consolidate his position as his generation's premier performer, Rob intends to take time off. He wants, he says, to find himself. Well, elusive as he can sometimes be, I hope he finds the cool, compassionate companion I meet. And when he does, could he please remind him that he still owes me £60?